The last bastion

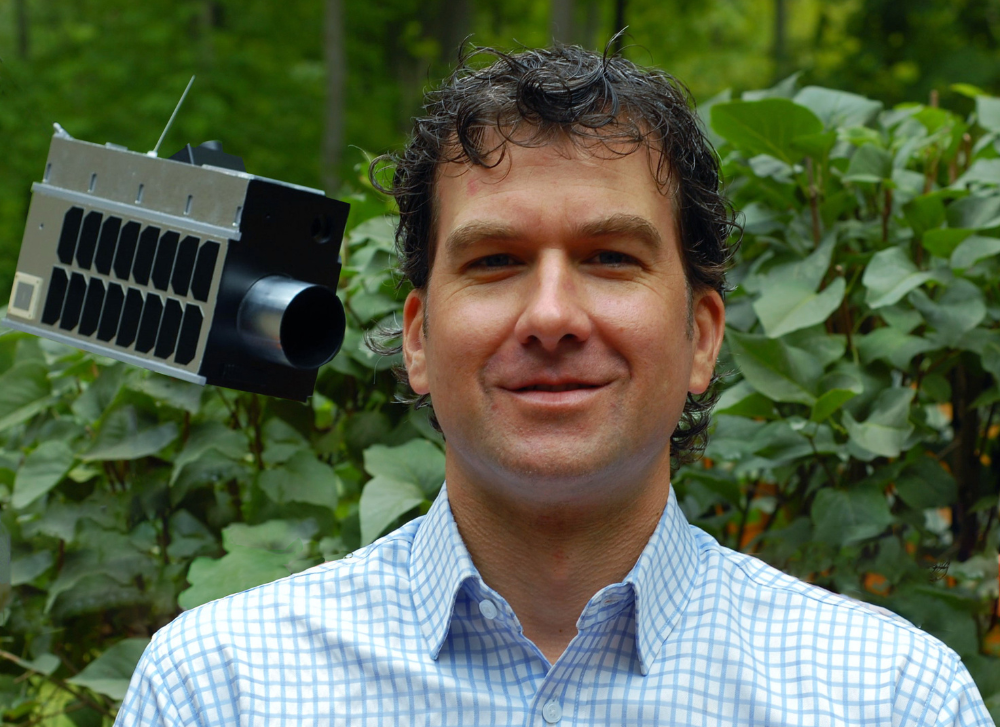

With his mane of steel wool held in a bridle by a ponytail gathered in a bun, Dominic Lamontagne has the look of a Percheron kicking into the stretchers. Not one to put the cart before the horse, this self-taught farmer is determined to uproot Quebec's agricultural prohibitions, which he describes as absurd.

Since he left Montreal with his wife and children to settle in Sainte-Lucie, in the Laurentians, in 2009, Dominic has been a promoter of small-scale ecological agriculture. On his land strewn with rocks and as large as 30 football fields (42 acres), there is no question of him imposing unreasonable animal pressure on the ecosystem and depending on inputs.

To counter the concentration of increasingly gigantic farms, the rural exodus, the abandonment of the territory, the closure of schools, grocery stores, restaurants and small slaughterhouses, he is not giving up. He demands the right for artisan farmers to operate farms a hundred times smaller than the norm. He is working hard to ensure that they can raise two cows, 200 laying hens and 500 chickens without having to go through the prohibitive quota system. He also claims to be able to cut them down, transform them and sell their surplus on site. In short, Dominic wants to make the smallest units of subsistence farms the last rampart of multi-productive rural agriculture.

Seven years ago, rebelling against the impossibility of selling his eggs at the market, his raw milk on the farm, of keeping even a single dairy cow or 100 chickens without paying the ruinous quotas, Dominic laid The Impossible Farm . His indictment against the repressive laws sought to make the political authorities, the powerful monopolistic federations and all the stakeholders who have a role to play in the standards linked to food production listen to reason.

Since then, the founder of the cannery In the face turned into an activist. It has become a voice for artisan farmers who wish to control all stages of production: from reproduction to breeding, from slaughter, to processing and sale of the fruit of their labor. He speaks at conferences, on TV and radio, publishes in the media, produces a television series with Amélie Dion, his wife, signs the preface to Rapailler our territories , this plea from Stéphane Gendron for a new rurality of the 21st century and many other things.

Dominic has done it again with the publication of a second book. The artisan farmer is, in short, a bible intended for small producers who would like to embark on this adventure to make a living without going into debt. In November, he promises us a third book. This time it will be a debate with vegans whom he accuses of taking to the streets claiming that meat is not food, but violence and animal suffering. It promises !

“ Don't talk to me about local produce and gastronomy in Quebec when I'm forbidden from buying chicken slaughtered on the farm and crème fraîche. We don't want to relive the Beautiful Stories of the countries above. We are asking that we be given back our ancestral freedom to trade in the products of our farms. The law on agricultural markets has favored monoculture producers to the detriment of artisanal farms. It is impossible for us to make a farm under supply management profitable by purchasing the quota at its market value. Personally, I do not want to sell my whole chicken. I want to roast it, cut it into quarters and make four plates for a country party. The idea is to seek out the added value that there is in the transformation of the raw product. I see my 300 over-quota chickens as 1200 meals. »

However, the fierce fight led by Dominic Lamontagne and other activists is not in vain. The father of two admits that under André Lamontagne, Minister of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, there is finally an opening. At the beginning of July, we learned that in August, a small slaughterhouse in Saint-Joachin de Shefford (Montérégie) would be able to offer slaughtering services for pasture-raised birds. A first for a Quebec solidarity cooperative. Dominic is also participating in a pilot project which will allow him to slaughter and sell his chickens on the farm. In a second part of the four-year pilot project, it will also be allowed to sell food products made from raw milk, other than cow's milk.

In theory, from the fall, the bearded 46-year-old could market his liver, gizzard and poultry confit on the farm or in a public market. But this summer, he prefers to focus on legalizing the process by working on a guide to good practices. This will allow those interested to know from the second year of the pilot project what to expect in terms of standards.

Even though he knows there will be plenty of other problems to solve, at the end of the day, he expects to have found ways to make slaughterhouses for $5 or $10,000. Need we tell you that he foresees a real revolution in country dining?